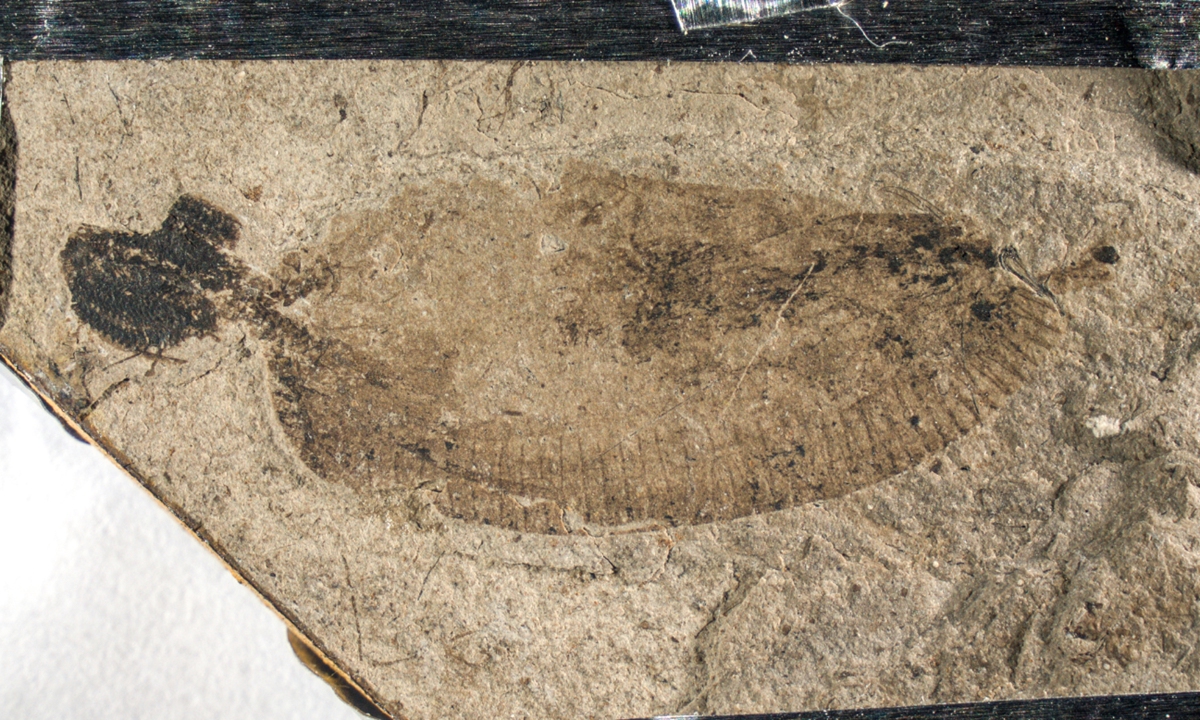

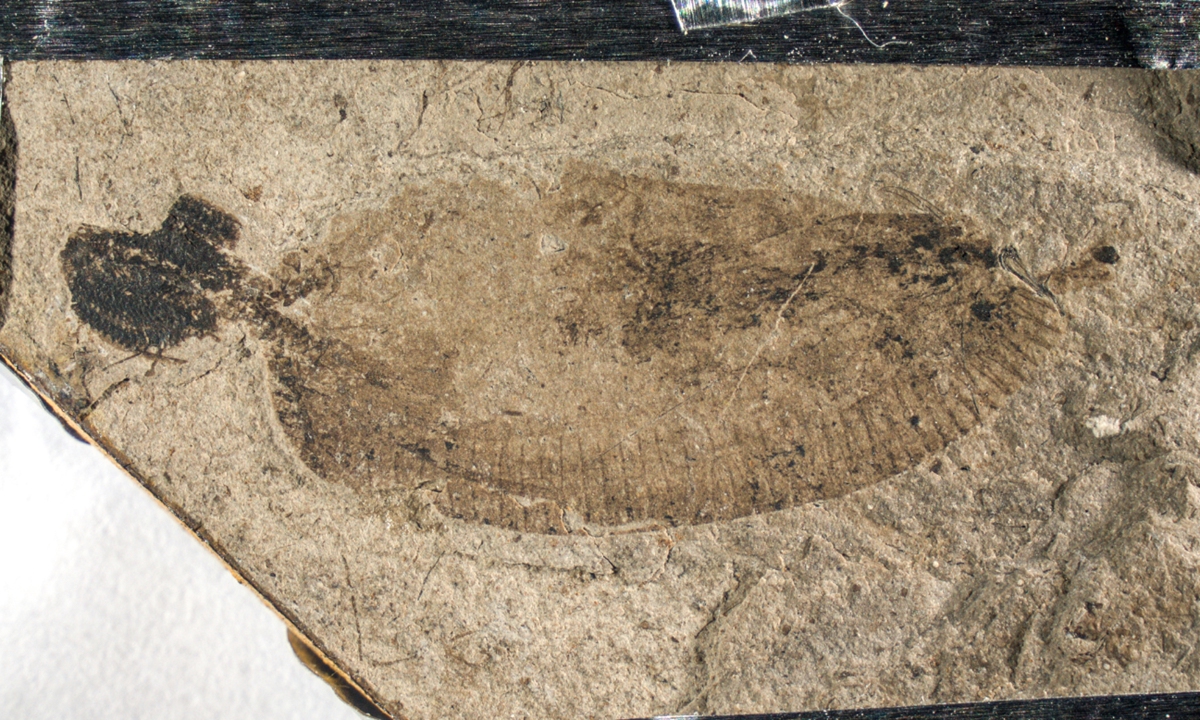

Photo: Courtesy of Wang Bo

A fossil acanthocephalan,

Juracanthocephalus, from the 160-million-year-old Daohugou Biota in North China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, has been discovered by a research team from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology Chinese Academy of Sciences. The discovery fills a crucial gap in the evolutionary history of thorny-headed worms and provides solid evidence for resolving the mystery of the origin of acanthocephala, the institute reported on Thursday.

"The discovery provides a crucial reference for understanding the evolutionary innovations and body plan of acanthocephalans," Wang Bo, leader of the research team, told the Global Times on Thursday.

"It's hooked proboscis and large body size suggest that it was an endoparasite that lived during the Jurassic period," he noted.

According to Wang, this fossil implies that acanthocephalans may have originated in terrestrial environments and diverged from Rotifera no later than the Middle Jurassic approximately 165 million years ago.

Acanthocephalans, commonly known as thorny-headed or spiny-headed worms, are a group of endoparasitic worms found in both marine and terrestrial ecosystems. These medically significant parasites infect a wide range of hosts, including humans, pigs, dogs, cats and fish, according to the institute.

Acanthocephalans are characterized by their worm-like body shape and a retractable proboscis armed with rows of recurved (backward-facing) hooks for anchoring to the digestive tracts of their hosts. Historically classified as a distinct animal phylum, their highly specialized bodies have led to ongoing debates regarding their phylogenetic position.

The phylum of animals comprises more than 30 phylum-level taxa, which together form the fundamental framework of animal evolution. The origin of each phylum has been a major focus of scientific research. However, despite being established over 200 years ago, the origin of acanthocephala has remained unresolved.

The fossil record of acanthocephalans is exceptionally sparse due to their soft bodies - which were less likely to fossilize than harder ones - and concealed habitats. Until now, the only known fossil evidence consisted of four putative acanthocephalan eggs discovered in the coprolites of a Late Cretaceous crocodyliform.

Due to the lack of body fossils, the origin and early evolution of acanthocephalans have remained poorly understood. The research team led by Wang has broken this deadlock.

Using scanning electron microscopy and energy-dispersive spectroscopy, the research team conducted a detailed anatomical analysis of

Juracanthocephalus and updated the morphological matrix of worm-like animals to support a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis.

Juracanthocephalus has a fusiform body divided into a proboscis, neck and trunk. The proboscis is equipped with strongly sclerotized, slightly curved hooks, while the ventral surface of the trunk features 38 lines of transverse, setaceous combs - a trait comparable to modern acanthocephalans. A possible alimentary tract is preserved in the proboscis, though no clear gut is visible in the trunk. The terminal end of the fossil displays a structure resembling the bursa of male acanthocephalans.

The results indicate that

Juracanthocephalus represents a transitional form between free-living, jawed rotifers and jawless, endoparasitic acanthocephalans, bridging an evolutionary gap. This finding provides the first direct fossil evidence to help resolve the long-standing mystery of acanthocephalan origins.

"This study underscores the importance of transitional fossils in elucidating radical morphological changes in animal body plans," Wang said.

"While molecular phylogenetics has revolutionized our understanding of evolutionary relationships,

Juracanthocephalus highlights the indispensable role of fossil evidence in reconstructing the history of life," he noted.

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the IUGS "Deep-time Digital Earth" Big Science Program, and the Jiangsu Innovation Support Plan for International Science and Technology Cooperation Programme.