The joint was jumping

While Shanghai has seen its jazz scene blooming with the emergence of local jazz artists as well as the establishment of new live jazz music venues over the past few decades, the history of this music genre in Shanghai goes back to the turn of the 20th century.

Jazz was first introduced to China during the Westernization Movement (1861-94), a nationwide campaign intended to enhance the country’s future by learning from its Western counterparts and developing cultural, military, economic and scientific advancements.

Holidays must not be occasions for bribery

My brother, a Party member and a low-level official in my hometown, told me that this year he has been summoned to many conferences about the “anti-mooncake” campaign.

Helping the medicine go down

Although Shanghai lagged behind Guangzhou in adopting Western medicine, its unique geographical location and economic and political status attracted the missionaries who began building churches and hospitals and eventually treating ordinary Chinese people. By 1910, Christian groups had built 14 hospitals in Shanghai, the most prosperous city in the Far East. Many of today’s city hospitals can trace their origins back to those early times including the Renji Hospital, the Ruijin Hospital, the Shanghai First People’s Hospital and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University.

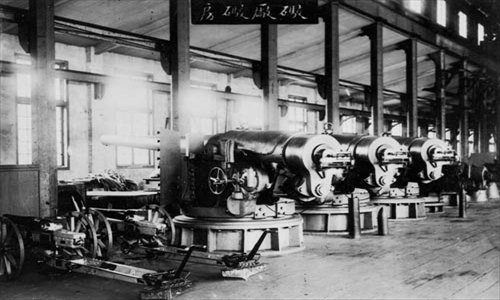

Guns, ships and science

Today the cranes and machinery that line the Huangpu River are a signpost to the Shanghai shipbuilding industry and home to some of the country’s largest shipbuilding companies. Modern shipbuilding began here 150 years ago as the country strengthened its military capabilities.

Singing for their suppers

For more than 400 years Chinese traditional opera has found a home in Shanghai. Sometimes a short-lived home, sometimes a turbulent home but opera has been at the city’s cultural heart for a long time. The traditions include Kunqu Opera, the elegant and soft Yueju Opera (a style from Zhejiang Province), and Huju Opera (Shanghai Opera). Peking Opera, the best-known variety of Chinese opera, is also at home here. Chinese opera blends dramatic stories with rarified musical styles, elaborate costumes, dancing, singing, mime and acrobatics.

The city goes front stage

Old Shanghai enjoyed a plethora of entertainment – dance halls, horse racing, clubs, bars, restaurants abounded. But for some, the theater was the place to be seen and to see plays and performances and enjoy the glamorous side of culture.

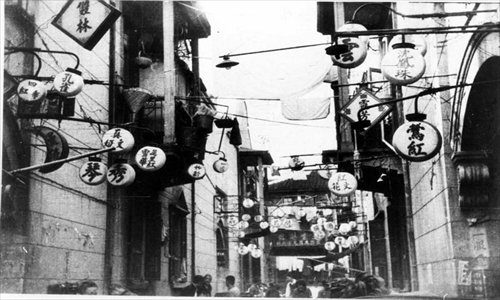

From brothels to books

Fuzhou Road is the bookshop street, the street that leads from the Bund to Xizang Road and is today where some of the city’s leading bookstores and art supply stores are to be found. It has had links with culture and literature almost since it came into being in the 1850s. Scores of newspaper offices were to be found here in Laobosanwoke Road as it was called in the early part of the 20th century. Albert Einstein once lectured there.

The sisters that shook Shanghai

“Once upon a time in distant China, there were three sisters. One loved money, one loved power, and one loved her country.” So opens The Soong Sisters, a 1997 film directed by Hong Kong filmmaker Mabel Cheung and starring Maggie Cheung, Michelle Yeoh, Vivian Wu and Jiang Wen.

Remnants of a city's dreams

If you visit the Shanghai University of Sport on Changhai Road in Yangpu district, the first building you’ll see upon entering the campus is a grand 1930s four-story Chinese palace. For architects and design experts, this building does not exactly belong in Shanghai. Shanghai buildings of this era are usually smaller and have the distinctive southern architectural design style.

Stars, scandals and sex

The 1930s was the time when Shanghai embraced the cinema and welcomed stars like Zhou along with others such as Ruan Lingyu and Hu Die. The passion and dramas they reveled in on screen, however, were often shaded by their real lives. They became an essential part of Shanghai’s life just as much as the Bund, the Paramount Ballroom or Nanjing Road.

A stamp of approval

To the right of Shanghai’s City God Temple in Huangpu district is a small street called Guanyi Street which can be translated roughly as Post Office Street. Few of the people who live in the street today would know why it was called this and fewer would know that 100 years ago this area of the former Nanshi district (now part of Huangpu district) was home to some of Shanghai’s post office forebears.

The orphanage of art

On the riverside near Zhaojiabang, south of Xujiahui, years of dredging the Puhui River, a major waterway for the area, had piled tons of river mud in a bend on the river. By the mid 1800s this formed a small hill which people called Tushanwan, or Tou-se-we in the Shanghai dialect (literally “the mud hill by the river”).

High times in higher education

Shanghai's two most prestigious universities, Fudan University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University, date back more than a century and although, now far apart geographically, were once linked by a humble ink bottle. This ordinary ink bottle saw one of the great universities blossom and grow while the other nearly disappeared from the city.

High life and low living

There's no real defined area now for Upper Shanghai. But the term, which is commonly used in the city, is not an invention of real estate agents or property developers. Throughout its history there has almost always been an upper and a lower Shanghai.

Enriching the city

More than most outsiders, Jewish businessmen left a mark on early Shanghai, a city that for many was a place of refuge from persecution – and for some a gold mine.

Walking with the writers

Duolun Road is best known as Shanghai's street of left-wing writers – many of the country's great and influential writers wrote and lived here in the 1920s and 1930s. But the 550-meter road, now a pedestrian zone, has had a checkered history in the city. Located in Hongkou district with the bustling commercial area of Sichuan Road North to the south and Hongkou Football Stadium at the north, Duolun Road has been running its L-shape course for just over a century.

Power, profits and poppies

Opium, the addictive brownish dream-making drug made from the opium poppy, was one of the driving forces of the good and the bad in Shanghai in the 19th century. Trade in opium, which almost turned much of China into a nation of addicts by the early 20th century, was the reason for Shanghai's unstoppable rise, and the key to the success of many of the lucrative hongs (foreign business houses) and affluent taipans (rich, powerful foreign businessmen).

The rise and fall of money shops

It's easy to see why Lujiazui in the Pudong New Area is China's banking capital. Banks and financial institutions tower next to each other here – a frenetic treasure house and close-knit home for 662 financial institutions. It's easy, too, to forget that Shanghai's financial success started with qianzhuang (small money shops) some 170 years ago when Shanghai's opening as a treaty port brought earthshaking changes to an age-old industry, laying the foundations for Shanghai's later commercial and financial development.